Aging and Autoimmune Disease

What happens to the immune system during aging that could lead to an increase in autoimmune disease risk? To take a deeper look, we spoke with two experts on aging and autoimmunity: Paul Robbins, co-director of the Masonic Institute on the Biology of Aging and Metabolism at the University of Minnesota, and Niharika Duggal, assistant professor at the Institute of Inflammation and Ageing at the University of Birmingham.

In 1969, the pathologist Roy Walford introduced the autoimmune theory of aging.

In this theory, he proposed that with age, the immune system becomes dysfunctional, autoimmune diseases increase, and our bodies don’t respond to infections as well (1).

It is not surprising that for many autoimmune diseases, age is considered a risk factor. A study published in 2023 looked at the incidence of 19 autoimmune diseases from 22 million people in the United Kingdom (2). They found that for several autoimmune diseases, including Graves’ disease, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, pernicious anaemia, and rheumatoid arthritis, incidence increased with age. Trends for other diseases weren’t as clear, with some diseases, like inflammatory bowel disease, having multiple peaks in incidence rates across ages.

What Does Aging Do To the Immune System?

Cellular Senescence

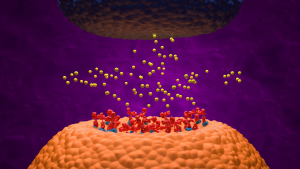

Aging also affects other cell types through a process known as cellular senescence, in which cells stop dividing but don’t die off. “Our lab believes that DNA damage, or genomic instability with age, is one of the key drivers of senescence,” says Robbins.

Once cells become senescent, they undergo several changes, including the secretion of a mixture of pro-inflammatory molecules that leads to an inflammatory response (3). This inflammation prompts the innate immune system to clear these cells. When we’re young, the immune system clears these senescent cells more easily. As we age, our immune system can’t clear them as well. This leads to a state of chronic, low-grade inflammation.

Immunosenescence: Immune System Remodeling and Dysfunction

Immunosenescence refers to the age-related remodeling of the immune system. It begins with subtle changes in our 20s and accelerates around age 50. Despite similarities in their names, immunosenescence is quite different from cellular senescence. “Overall, what we’re seeing is a decline in the ability of the immune system to fight off pathogens,” says Duggal. “On the other hand, we’re also seeing that the immune system is in this persistent activated state due to chronic exposure to pathogens across life course. This persistent activation could be inducing a state of cellular senescence and making these cells more proinflammatory in nature.”

During immunosenescence, not all cells are affected the same way. “Depending on which cells we look at, things look different,” says Duggal. For example, neutrophils, which have roles in autoimmunity and in clearing bacterial infections, don’t decline in terms of numbers but decline in terms of function. For T cells, there’s a remodeling in the different subsets of T cells. “We see an expansion of circulating pro-inflammatory senescent T cells, for example,” Duggal adds. In addition, as we age, the thymus also shrinks and produces fewer naive T cells. All in all, these changes in the immune system as we age lead to immune dysfunction.

Inflammaging: Chronic Low Levels of Inflammation

Inflammaging is the chronic, low levels of systemic inflammation that’s associated with aging. This inflammation is partly caused by an increase in the innate immune response leading to the secretion of pro-inflammatory substances (4) and senescent cells themselves secrete pro-inflammatory molecules.

This chronic inflammation, while at a low level, damages healthy tissues over time, leading to an increased risk of diseases including heart disease, Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease (5, 6, 7).

Connections Between Autoimmunity and Neurodegenerative Diseases

We normally think of diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease as neurodegenerative diseases, but these diseases may actually have characteristics of autoimmune diseases. Much of the research in this area is relatively recent. In 2014, David Sulzer’s group from Columbia University published their finding that neuronal death seen in Parkinson’s occurs because our immune system mistakenly targets neurons as non-self (8). Other work finds that a type of T cells called Th17 lymphocytes attack dopamine cells in Parkinson’s patients but not in people without Parkinson’s (9).

There’s also some evidence of autoimmune aspects of Alzheimer’s disease. The idea comes from the fact that in response to a pathogen, amyloid beta is released and launches a cascade of immune responses. But because of electrophysiological similarities between bacteria and neurons, they can mistakenly attack neurons (10). Other studies find that those admitted to a hospital for autoimmune diseases are more likely to be admitted to a hospital later in life.

As of now, neither of these diseases are primarily known as autoimmune diseases, but the connections between these diseases and autoimmunity are becoming more apparent.

How Can I Keep My Immune System Healthy Through Aging?

Lifestyle Changes

We’ve probably all heard about the health benefits that reducing stress, eating well, sleeping well, and being active have on our bodies. But what’s the evidence for these benefits, and can these habits help keep our immune system functioning well? Duggal’s lab studies these connections and finds that many lifestyle factors contribute to the rate of immune aging.

She explains that there is evidence that physical activity and healthy eating positively influence immune aging, while chronic stress has a negative impact on the immune aging trajectory. One study from her lab finds a link between physical activity and reduced immunosenescence in the body (11). Another study finds that the Mediterranean diet is associated with a lower immunological age (12).

Senolytic Drugs to Clear Senescent Cells

A growing area of age-related drug development is senolytics. These drugs target and clear senescent cells from the body. Recent efforts looking at senolytics have found that they decrease the severity of autoimmune encephalomyelitis in preclinical models (13). “If we can make senolytic drugs better and more effective, I think that’s going to have tremendous potential,” says Robbins.

Senolytic compounds are often found in plant-based foods. “They actually can reduce your senescent cell burden if you take enough of it,” says Robbins. “Whether you get enough in fruits and vegetables is still a question, but I think you probably can. That will reduce your senescent cell burden, either of your immune cells or other cells, at least a little, which then indirectly improves your immune system.”

However, it’s unclear how helpful senolytics can be. Robbins says that many of the supplements that are meant to boost immune health have been shown to work in preclinical models, but not in humans. And if you don’t have a lot of senescent cells in your body, senolytic drugs won’t help you that much.

Regardless, there’s no easy fix to boost immune health – you can’t just take supplements and ignore your diet or exercise. “Our usual take-home message is that there’s not one simple solution. It’s a more holistic approach,” says Duggal.

Future Research in Aging and Autoimmunity

There are still a lot of unknowns when it comes to aging and the immune system (even aging researchers can’t agree on what aging exactly is or when it starts (13). Recent efforts from the NIH-funded SenNet consortium include mapping where cells go senescent across multiple tissue types in the body. “What we’re realizing is that senescence is far more complicated than we thought,” says Robbins. “Through SenNet, we’ll have the opportunity to start to look at this in different disease contexts, both in mice and in humans.”

While the aging process is already a complicated area of study, considering autoimmune diseases in the context of aging adds another level of complexity. It’s another reminder of the interconnectedness that the seemingly disparate systems and diseases within the human body are actually quite connected.

About the Author

Sources

- Article Sources

Diggs, J. Autoimmune Theory of Aging. In Encyclopedia of Aging and Public Health (pp. 143–144). Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-33754-8_46

Conrad, N., Misra, S., Verbakel, J. Y., Verbeke, G., Molenberghs, G., Taylor, P. N., Mason, J., Sattar, N., McMurray, J. J. V., McInnes, I. B., Khunti, K., & Cambridge, G. (2023). Incidence, prevalence, and co-occurrence of autoimmune disorders over time and by age, sex, and socioeconomic status: a population-based cohort study of 22 million individuals in the UK. Lancet (London, England), 401(10391), 1878–1890. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00457-9

Herranz, N., & Gil, J. (2018). Mechanisms and functions of cellular senescence. The Journal of clinical investigation, 128(4), 1238–1246. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI95148

Rasa, S. M. M., Annunziata, F., Krepelova, A., Nunna, S., Omrani, O., Gebert, N., Adam, L., Käppel, S., Höhn, S., Donati, G., Jurkowski, T. P., Rudolph, K. L., Ori, A., & Neri, F. (2022). Inflammaging is driven by upregulation of innate immune receptors and systemic interferon signaling and is ameliorated by dietary restriction. Cell reports, 39(13), 111017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2022.111017

Barcena, M. L., Aslam, M., Pozdniakova, S., Norman, K., & Ladilov, Y. (2022). Cardiovascular Inflammaging: Mechanisms and Translational Aspects. Cells, 11(6), 1010. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11061010

Kosyreva, A. M., Sentyabreva, A. V., Tsvetkov, I. S., & Makarova, O. V. (2022). Alzheimer’s Disease and Inflammaging. Brain sciences, 12(9), 1237. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12091237

Calabrese, V., Santoro, A., Monti, D., Crupi, R., Di Paola, R., Latteri, S., Cuzzocrea, S., Zappia, M., Giordano, J., Calabrese, E. J., & Franceschi, C. (2018). Aging and Parkinson’s Disease: Inflammaging, neuroinflammation and biological remodeling as key factors in pathogenesis. Free radical biology & medicine, 115, 80–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.10.379

Cebrián, C., Zucca, F. A., Mauri, P., Steinbeck, J. A., Studer, L., Scherzer, C. R., Kanter, E., Budhu, S., Mandelbaum, J., Vonsattel, J. P., Zecca, L., Loike, J. D., & Sulzer, D. (2014). MHC-I expression renders catecholaminergic neurons susceptible to T-cell-mediated degeneration. Nature communications, 5, 3633. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4633

Sommer, A., Marxreiter, F., Krach, F., Fadler, T., Grosch, J., Maroni, M., Graef, D., Eberhardt, E., Riemenschneider, M. J., Yeo, G. W., Kohl, Z., Xiang, W., Gage, F. H., Winkler, J., Prots, I., & Winner, B. (2019). Th17 Lymphocytes Induce Neuronal Cell Death in a Human iPSC-Based Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Cell stem cell, 24(6), 1006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2019.04.019

Weaver D. F. (2023). Alzheimer’s disease as an innate autoimmune disease (AD2): A new molecular paradigm. Alzheimer’s & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 19(3), 1086–1098. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12789

Duggal, N. A., Pollock, R. D., Lazarus, N. R., Harridge, S., & Lord, J. M. (2018). Major features of immunesenescence, including reduced thymic output, are ameliorated by high levels of physical activity in adulthood. Aging cell, 17(2), e12750. https://doi.org/10.1111/acel.12750

Conway, J., Acharjee, A., & Duggal, N. A. (2024). Integrated analysis revealing novel associations between dietary patterns and the immune system in older adults. Integrative biology : quantitative biosciences from nano to macro, 16, zyae010. https://doi.org/10.1093/intbio/zyae010

Drake, S. S., Zaman, A., Gianfelice, C., Hua, E. M., Heale, K., Afanasiev, E., Klement, W., Stratton, J. A., Prat, A., Zandee, S., & Fournier, A. E. (2024). Senolytic treatment diminishes microglia and decreases severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Journal of neuroinflammation, 21(1), 283. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-024-03278-2

Gladyshev, V. N., Anderson, B., Barlit, H., Barré, B., Beck, S., Behrouz, B., Belsky, D. W., Chaix, A., Chamoli, M., Chen, B. H., Cheng, K., Chuprin, J., Churchill, G. A., Cipriano, A., Colville, A., Deelen, J., Deigin, Y., Edmonds, K. K., English, B. W., Fang, R., … Zhavoronkov, A. (2024). Disagreement on foundational principles of biological aging. PNAS nexus, 3(12), pgae499. https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgae499